In the shadowed annals of history, few dates evoke as much dread as Friday the 13th. For millions, it is a day to avoid black cats, ladders, and shattered mirrors—a superstitious fog that thickens the air with unease. But beneath the pop culture veneer of slasher films and horror tropes lies a darker, blood-soaked origin: the brutal suppression of the Knights Templar on October 13, 1307. Often whispered about in conspiracy circles as the “massacre of the masons,” this event wasn’t just the fall of a medieval military order. It was the systematic destruction of an organization whose legacy—real or imagined—would echo through centuries, fueling myths of secret societies, hidden treasures, and unbreakable oaths.

The Rise of the Warrior-Monks

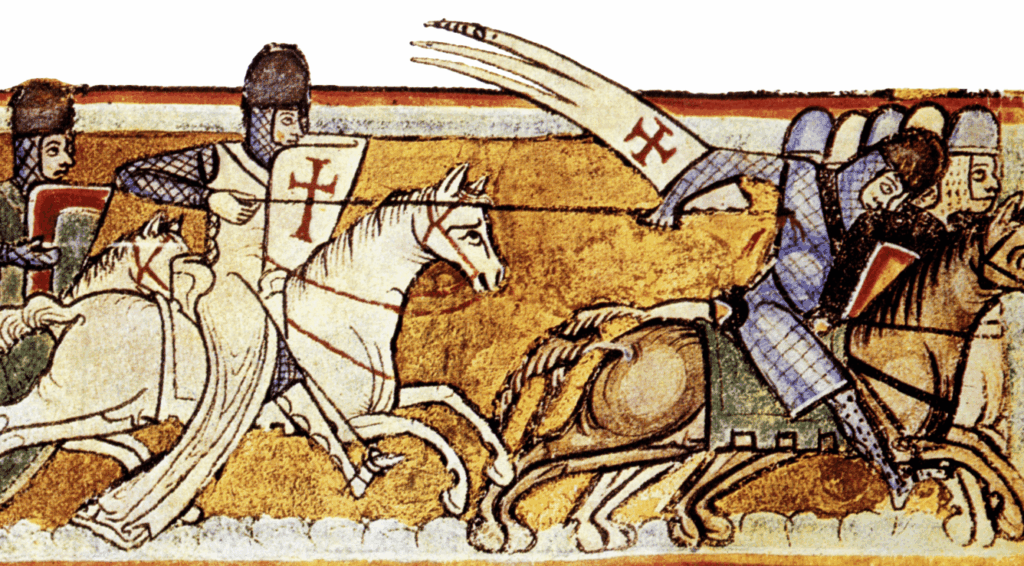

To understand the tragedy, we must first meet the men at its center. The Poor Fellow-Soldiers of Christ and of the Temple of Solomon—better known as the Knights Templar—were born in the crucible of the Crusades. Founded around 1119 by Hugues de Payens, a small band of French knights vowed to protect Christian pilgrims traveling to the Holy Land. They took monastic vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience, but their battlefield prowess turned them into legends.

Backed by the Pope and European royalty, the Templars grew into a formidable force. They built castles across the Levant, fought with fanatical zeal in battles like the Siege of Ascalon, and developed an innovative banking system that made them the medieval equivalent of a multinational corporation. Kings deposited funds in Paris and withdrew them in Jerusalem. Their white mantles emblazoned with the red cross became symbols of divine favor—and untouchable wealth.

By the late 13th century, however, the Crusades had crumbled. The fall of Acre in 1291 marked the end of Christian holdings in the Holy Land. The Templars retreated to Europe, their military purpose obsolete, but their riches intact. This was their fatal mistake.

The Greedy King and the Dawn Raid

Enter King Philip IV of France, “the Fair”—a ruler as handsome as he was ruthless. Deep in debt from wars and extravagance, Philip eyed the Templars’ vast estates, banks, and treasures with predatory hunger. He had already expelled France’s Jews and seized their assets. The Templars, with their papal immunity and enormous holdings, were next.

In September 1307, Philip’s agents fanned out across the kingdom with sealed orders. At dawn on Friday, October 13—a date chosen for its symbolic weight—thousands of soldiers descended on Templar preceptories. In Paris alone, Grand Master Jacques de Molay and hundreds of knights were dragged from their beds. The operation was meticulously coordinated: simultaneous arrests from Cyprus to England (though resistance varied elsewhere). Over 2,000 Templars were eventually rounded up in France.

The charges were as lurid as they were fabricated: heresy, idolatry, sodomy, and devil worship. Accusers claimed the knights spat on the cross during initiation, worshipped a bearded head called Baphomet, and engaged in obscene rituals. Philip, in league with the weak Pope Clement V (his former advisor), framed it as a holy purge. In reality, it was a smash-and-grab heist.

The Massacre Unfolds: Torture, Flames, and Silence

What followed was one of history’s most methodical inquisitions—a true “massacre of the masons,” if we view the Templars through the lens of their symbolic descendants. Imprisoned in damp dungeons, the knights endured horrors designed to break body and soul. The strappado hoisted men by wrists tied behind their backs, dislocating shoulders with sickening pops. Feet were slathered in oil and roasted over fires. The rack stretched limbs until joints popped. Under such agony, most confessed to anything demanded of them.

By 1310, 54 Templars burned at the stake in a single day outside Paris, their screams mingling with the crackle of flames. The order was formally dissolved in 1312 by papal decree, its assets “transferred” to the rival Knights Hospitaller—though Philip pocketed much of the gold. Two years later, on March 18, 1314, Jacques de Molay met his end. Dragged to a pyre on an island in the Seine, the 70-year-old Grand Master recanted his tortured confession. “God knows who is in the wrong and has sinned,” he proclaimed. “Misfortune will soon befall those who have unjustly condemned us.”

Legend says de Molay’s curse rang out as the flames consumed him: Philip and Clement would follow him to the grave within a year. Both did—Philip from a hunting accident or stroke in November 1314, Clement from illness months earlier. The curse became gospel in Templar lore.

From Templars to Masons: The Secret Survival

Here is where the story twists into the realm of the “masons.” In esoteric traditions and conspiracy theories, the Templars did not simply vanish. Fugitives allegedly fled to Scotland, Portugal, and beyond, carrying their secrets—architectural knowledge, sacred geometry, and perhaps even the Holy Grail or Ark of the Covenant. These “masons” (a term evoking their role as builders of fortifications and cathedrals) are said to have seeded the guilds that evolved into modern Freemasonry.

Masonic orders like the Knights Templar degree in the York Rite explicitly invoke the medieval knights. Symbols overlap: the all-seeing eye, the square and compass, even the red cross. Some historians dismiss this as 18th-century romanticism, a way for Enlightenment-era Masons to claim ancient prestige. Yet the parallels are tantalizing. Did persecuted Templars go underground, preserving their rites in stone-carvers’ lodges? Or was the “massacre” a deliberate strike against a brotherhood that threatened royal and papal power?

Whatever the truth, the event cemented Friday the 13th as a harbinger of doom in the popular imagination—though scholars note the superstition crystallized later, in the 19th and early 20th centuries, amplified by novels like Friday, the Thirteenth.

The Echoes Today

Centuries later, the massacre’s shadow lingers. Paraskevidekatriaphobia—the fear of Friday the 13th—affects millions, costing businesses billions in avoided travel and decisions. Yet for those who delve deeper, it is a reminder of how power crushes the independent. The Templars were neither saints nor demons; they were men of faith and finance, undone by greed.

In Masonic temples and history books alike, their story endures as a cautionary tale: empires fall, but ideas—and perhaps curses—persist. So the next time the calendar aligns on that fateful Friday, pause. Listen for the distant clash of swords, the creak of dungeon doors, the final words of a dying master. The masons may have been massacred, but their legend refuses to die.